Fuck AI

Or, how higher ed ends with a whimper

In his now famous 2005 commencement speech at Kenyon College, later published as “This Is Water,” David Foster Wallace offers a subtle rethinking of the cliché that a liberal arts education is supposed to teach you “how to think”:

If you’re like me as a student, you’ve never liked hearing this, and you tend to feel a bit insulted by the claim that you needed anybody to teach you how to think, since the fact that you even got admitted to a college this good seems like proof that you already know how to think. But I’m going to posit to you that the liberal arts cliché turns out not to be insulting at all, because the really significant education in thinking that we’re supposed to get in a place like this isn’t really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about.

As Wallace later points out, it all boils down to a certain kind of freedom:

[T]here are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talk about much in the great outside world of wanting and achieving…. The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.

There’s a ton packed into this. You might wonder why “attention and awareness and discipline” has anything to do with “being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.” The answer, I think, runs deep, and has everything to do with human nature. But set that aside. Focus on the question of focus.

To do anything well you need to pay attention for a sustained period of time. To do this, you need to be able to resist the pull of distraction. And to do this, it helps to create a peaceful, distraction-free environment. Of course, no environment is fully distraction-free. Still, you can make efforts, improve your odds, by finding a quiet workspace, leaving the smartphone behind, and so on. It’s like dieting. If you want to lose weight, don’t go shopping when you’re hungry and don’t pack the freezer full of ice cream.

But whatever you do, you’ll still be there with your body, its aches and pains, and your chattering mind, serving up thought after distracting thought. As they say: wherever you go, there you are. This is why paying attention for any period of time is a skill. You need to learn how to manage the inevitable distractions that come with having a finite mind lodged in an achy-breaky body. There are ways to practice and to build this skill. And DFW is right: without it, you’re pretty much fucked, for a variety of reasons.

Which brings us back to education.

Overall, I think I agree with Wallace. But I think he could just have just as easily put his point this way: There is a difference between thinking—in the sense of managing the basics—and thinking well. Everyone who speaks a language fluently can follow and construct simple chains of reasoning and recognize (very) obvious logical fallacies. In this sense, they know how to think. But thinking well is thinking deeply, and this means: slowing down enough to ask probing questions that might seem too obvious to bother with, and being very careful with how you reply. In reading and writing, it means paying close, critical attention to the semantic relationships in and between sentences, paragraphs, sections, chapters, and so on. In daily life, it means being aware of the trajectory of your thoughts and asking whether they are justified, reasonable, healthy, or just a product of blind, reactive habit. These are skills. And cultivating them requires “attention and awareness and discipline.”

However…

In June 2007, two years after Wallace’s speech and one year before his suicide, Apple introduced the iPhone. This was also the year I started my first full-time teaching position.

Over the next decade, social media, the attention economy, and surveillance capitalism blossomed into the grand clusterfuck that now consumes us. I won’t belabor the point. We all know it. It’s been detailed and discussed ad nauseum: there are forces of enormous, world-historic power directed at capturing our attention—that is, at distracting us—and eroding our capacity to focus. Their bottom-lines depend entirely on our inability to govern what we pay attention to. They offer click- and scroll-bait, and we are the eager, vulnerable prey.

This has had profound effects on almost every aspect of our lives, and higher ed is no exception. Year to year, things didn’t seem to change very much. Like the proverbial frog in hot water, it was only once conditions were getting uncomfortable that we realized something bad had been happening.

So, fast-forward 15 years, to Fall Semester 2022.

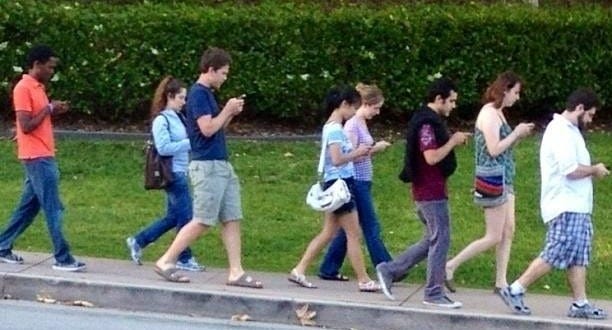

A first-year college student at an elite undergraduate institution. Grew up with a smartphone. Can’t imagine reading anything (maybe Harry Potter?) for an hour straight. Can’t imagine not having the phone on the library table while studying. Can’t walk across campus without glancing at the phone every few seconds. (I’m not exaggerating. This is the standard walking posture of today’s college student:1

Even when they’re not looking at their phones, they’re holding them in their hands, ready to go.)

Imagine assigning this student a five- to seven-page paper on the lessons of Plato’s Apology. This would have been common enough in an introductory philosophy course in 2007. But how do you think the average smartphone-bred, post-COVID student would do on this assignment? (Poorly.) Moreover, how do you think they would feel faced with this assignment? (Panicked.) But don’t worry: this student didn’t show up overnight, and our educational practices evolved to accommodate them. First, we inflated grades. Second, we simplified assignments. In so doing, we made sure we had fewer unhappy students in office hours, fewer complaints to the Dean, and less tuition lost to dropouts. Of course, everyone was learning less, too. But only the professors really seemed to notice.

And then, suddenly…

November, 2022: Enter generative AI.

At first, it was pretty easy to tell what was human undergraduate and what was AI. But now we can’t—at least not reliably enough. So, as far as I’m concerned, this means: no more take-home written work. Which basically means: no more serious written work. And a great many of my colleagues have come to the same conclusion.

In higher-level courses with students that I know and (mostly) trust? Okay, I’ll still assign papers. Carefully. But at the introductory level? No way.

Generative AI such as ChatGPT is presented to us—and widely used—as a cognitive prosthesis. It is presented—and used—as a way of getting your thinking and writing done on the cheap. But the fact is that generative AI systems don’t think. They also don’t write. So, they can’t do either of these things for you. (Instead: they can generate convincing illusions of doing these things.) What this means is that they are not cognitive shortcuts, they are evasions of cognition altogether.2

There are many, many issues to be discussed here. But what I want to focus on now is how generative AI both capitalizes on and functions as a cosmetic cover-up for the damage done to our minds by the smartphone, the attention economy, and surveillance capitalism. Problem: those things made it harder for us to think. Solution: generative AI allows us to evade thinking altogether. Brilliant! From the outside, it looks like repair. However, beneath the surface, the reality is an acceleration of decay. The essays suddenly look stronger, but the thinking behind them is even more impoverished. In this respect, AI is a cheap dodge.

But what, really, is lost? Why, really, should we care?

Shouldn’t I just learn to teach with AI? After all, it’s the future, right?

What do we really lose when accept the gambit offered by the AI evangelists?

Is it too much to say: everything? Maybe. But maybe not.

For one thing, generative AI is repetitive AI: it is trained on human data. Its “imagination” is limited to what humans have already said and done. So, if we use AI to plan for the future, recommend policy, and so on, we should expect the future to look very much like the past. No, thank you.3

Second, the only beings fully qualified to evaluate what AI systems generate are humans who can think independently of those AI systems. This is why “writing with AI” is impossible unless you can already write without it. Otherwise, you’re just looking on while the AI generates text for you. And if this is all you do, then chances are very slim that you will ever learn how to write a carefully constructed, thoughtful essay, which, in turn, means that you will never be qualified to evaluate what the AI generates. There’s no easy way out of this vicious circle. You have to do the hard work on your own. And yeah, it’s hard work, especially if your attentional capacities have already been eroded—or were never developed—thanks to the smartphone glued to your palm.4

Third, farming out your capacity to think deprives you of some (most?) of the highest experiences available to human beings. Let me explain. (Briefly. I’ll say a lot more about this in some future posts.)

My current primary research project focuses on wonder. This is a topic that is central to the history of philosophy and the history of science, but it has received hardly any attention over the last couple of centuries. (Psychologists have worked a lot recently on awe, but I think wonder is importantly different—and more fundamental.) For present purposes, the key idea is that wonder involves experiencing your own cognitive limits. But to do this you actually have to reach them. And this requires thinking for yourself. This means that any technology that erodes your ability to think erodes your ability to experience wonder, and any technology that makes thinking less habitual makes wonder less common. And this is a problem because many of the things that we value most, such as art and interpersonal love, as well as scientific and philosophical inquiry, depend essentially on our capacity to wonder.

In a slogan: a wonderless world is a loveless, artless, empty world.

And AI is a wonder-killer.

So, yeah: Fuck AI.5

Returning, in conclusion, to Wallace:

If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.

Learning to think well, to slow your thoughts down, to ask questions, and to be careful, oh-so-careful, about how you answer them—this is what a liberal arts education is about. This is real “critical thinking.” And it matters not just because it’s important for a democratic citizenry. It matters because it’s essential to living the best possible human life. It matters because it’s a gateway to wonder. But as for the state of higher ed now? A pale shadow of its promise, the dying whimpers of a beautiful ideal. Perhaps it can be resurrected, but the forces lined up against it are massive, massive, massive. I don’t have much hope.

Oh, right: welcome to my substack. If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe. There’s more to come.

Of course, it’s not just college students. And it’s so common there’s even a name for it: “distracted walking”—and it’s led to a significant increase in pedestrian fatalities.

I plan to write more on this in later posts. Here I take it for granted.

On this point, see Shannon Vallor’s excellent The AI Mirror.

What to do about AI in schools? As far as I’m concerned there is only one solution: create technological oases and make students spend time in them. Make them read there. Make them write there. Sounds rough, right? Not really. It sounds just like the libraries we used to study in. <mic drop>

My complaints about AI (and smartphones, etc.) aren’t technophobic. They also aren’t science-phobic. In the 19th century, Romantics complained that scientific explanation would destroy wonder. I think this is a mistake. What destroys wonder is not explanation, but the cessation of thinking. And I’m perfectly happy with the use of generative AI when trained on limited data sets in limited contexts to solve specific problems—such as in scientific research on, say, protein folding. But setting aside all of the problems with the AI industry (e.g., intellectual theft, environmental destruction, labor exploitation, and trillions of misspent dollars that might have been used for real benefit), I think that the unregulated creation and distribution of all-purpose generative AI is a big, big mistake.